Habit 1: Research and Prioritize

#managing_others Too many companies want to work hard and get lucky, but they forget what Seneca once said: "Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity."

This article is Part 2 of 4 in the 3 habits of highly effective organizations series.

There are so many things to do - how do organizations decide on what to do? If you're a small company, you have big ambitions but limited resources. If you're a big company, you may have extensive resources but need to collaborate across the company to get anything meaningful done. In both cases, teams yearn to understand what it is that they should be working on at any point in time that is most helpful.

Three prioritization dimensions: Impact, Probability of Success, and Time

Highly effective organizations understand luck happens when preparation meets opportunity. They execute by focusing on a small number of priorities determined by asking themselves three basic questions:

Will the work matter?

Will we succeed?

When will we see benefits?

Loosely, these questions break down into 3 specific dimensions: impact, probability of success, and time.

Impact

Organizations can pursue any number of strategic projects at any time that may add value. However, some projects may add more value than others. The impact of a project for a company may be felt in a few ways, including but not limited to:

Revenue - how much incremental money will we collect from customers?

Expense - how much money will we save?

Efficiency - how much more work can we get done?

Because there is a trade-off between projects, I try to guide my stakeholders and managers to think in terms of dollars. Some projects removed from dollars, such as projects that have an efficiency impact, may still yield some hypothetical dollar value if the efficiency gains impact an expense function, a revenue function, or both.

Probability of Success

Some projects are inherently riskier than others. In some cases, a project may yield no positive outcomes despite the potential impact it could have had on the business. We’ve all been there, and that’s frustrating, but effective organizations seek to take calculated risks. A few factors that may impact the chances of a project being impactful include:

Personnel - does the organization have the right expertise to succeed?

Unknowns - what are the known unknowns that may impact a project?

Budget - will cash be a limiting factor in implementing the project?

Competition - will we face competition?

In fact, there are probably a vast number of factors that may impact a project's chance of success.

Time

Projects take time, but what causes a project to take more or less time can vary. But wait! You might observe that projects that take more time are generally more expensive, and the longer a project takes, the riskier it is, so why have an explicit viewpoint on time when assessing a project?

While these points are both true, my observation is that effective organizations have an explicit discussion about time for three reasons.

First, it is often easier to load the cost of time into the project decision explicitly rather than deduct the cost of time (e.g., labor) from impact calculations.

Second, other issues besides time can also impact the probability of success, so separating a probability of success discussion from time is useful to highlight the non-obvious.

Finally, there are several other factors related to a project that may impact time, including:

Personnel - is the project limited to certain individuals that can do the work, certain groups that can do the work, or the number of people that can do the work?

Partnerships - does the project have external dependencies with partners and their ability to deliver?

Event Commitments - is the project required to be delivered by a specific date for an event?

Internal Dependencies - does the project depend on existing projects to reach a certain state of completion?

Invariably, time-related factors can play a large role in the practical realities of when a project can be delivered. When organizations fail to have an explicit conversation about the impact of time on a project, they lose the ability to predict how their activities will impact the business.

Resources?

But what about resources? It takes people and money to execute projects, so why isn't that calculated explicitly? While it is true that resources are needed to execute projects, I believe a productive discussion is ideally held without the discussion of resources for two specific reasons.

First, by factoring in resource availability upfront, leaders tend to anchor their decisions around the current status quo. For example, if only 10 engineers will free up in the next month, there's a temptation to reframe what could be done to just what 10 engineers can do - but this ignores the simple fact that it may be prudent to stop even more projects to free up resources.

Of course, if it's obvious that the proposed ambition exceeds the entire labor pool's size, then that's another story, but that seldom happens in my experience.

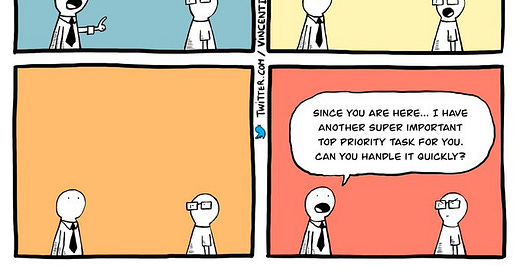

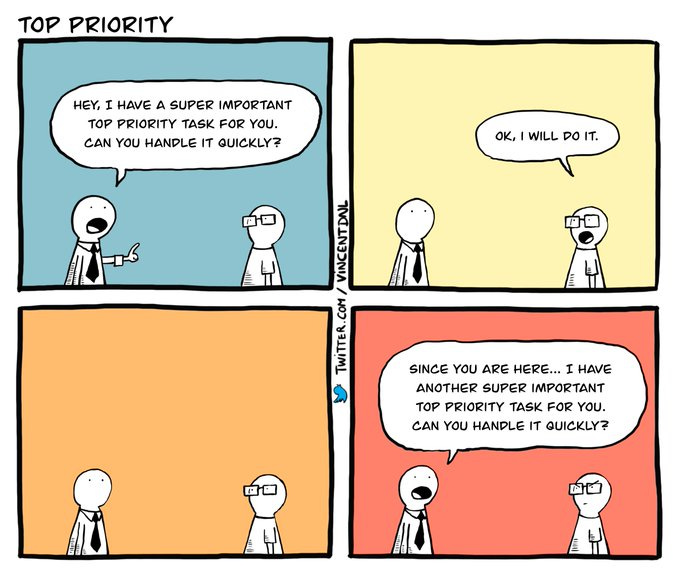

In fact, the more common tendency is for organizations large and small to think they can start many things at once.

This leads me to my second reason, why I encourage leaders to ignore resource calculations. When resources are factored into decisions, there's a tendency for leaders to be seduced into thinking that a clever reconfiguration of people and funds can magically maximize the value of the available team. Instead, people tackle more projects than they should. In these situations, teams find themselves trying to force-fit their commitments in a delicately coordinated dance that is awkward and creates collaboration overhead.

Ignore this temptation by skipping the resource conversation altogether. The truth is that not everyone's work has to fit neatly within the company's project priorities.

Even modest-sized organizations have "run the business" activities that are critical and need to be done well. Starving an organization of their ability to run the business is like withholding water from a person. In both cases, they might die. So, it is important to create slack in the organization to run the business and empower teams to improve how they do the basics. This ensures that new initiatives do not materially harm the organization's ability to do this by taking up all of the resource slack.

Steps to success

How does one go about the research effort to vet through the list of candidate projects with three dimensions to optimize? There are several ways to do this, and I'll outline my two-step process.

Step 1: Score every candidate project along with Impact X Probability of Success

I've seen lists of candidate projects that have had hundreds of entries! I feel your pain when it comes to working with teams that struggle to focus. In those situations, I find it necessary to quickly narrow down what to focus on by guiding my partners on an exercise to score each project along impact and probability of success by making them identify where each project goes in the following 2x2:

While it's true any combination of impact, probability of success and time could be used to score projects in a 2x2 - I find that stakeholders can make reasonably accurate judgments about impact and probability of success quickly.

Once you have your results, here's how you interpret them:

Low Impact x Low Probability of Success: If a project has a low financial impact and the team has a low chance of making it happen, don't do it and don't revisit it in future discussions unless you have new information.

High Impact x High Probability of Success: If a project has a high financial impact and a high probability of success, these projects are strong contenders to pursue and should be noted.

Low Impact x High Probability of Success or High Impact x Low Probability of Success: If a project falls into either of these categories, I recommend flagging them for review with a bias for removing items off the list that the organization isn't excited about doing.

Step 2: Score the remaining list against time

After step 1, you should have a list of potential projects that fall into one of three categories:

High Impact x High Probability of Success

Low Impact x High Probability of Success

High Impact x Low Probability of Success

For each project, time now needs to be factored into the decision. In most cases, key stakeholders and executives are typically incapable of making accurate assessments on these matters, so during the planning process, this is typically when the extended team of subject matter experts needs to chime in. The team's estimates mustn't be a precision exercise since the work it takes to make a precise estimate is time-consuming. However, they should be precise enough that stakeholders should understand how many quarters a project will take from start to finish.

If any proposed project takes more than a year, those projects need to be broken down into manageable proposals that add value to the business.

Upon completion of this exercise, I rank projects according to the following algorithm:

High Impact x High Probability of Success x 1 quarter

High Impact x High Probability of Success x 2 quarter

High Impact x High Probability of Success x 3 quarter

High Impact x High Probability of Success x 4 quarter

High Impact x Low Probability of Success x 1 quarter

Low Impact x High Probability of Success x 1 quarter

My logic is that short projects allow an organization to benefit from the project sooner and are therefore more valuable. For the projects that were on the bubble either because of questionable chances of success or impact, I think pursuing potentially high impact projects that will finish in a quarter is worth the gamble. If the project fails, at least it fails fast. By the same logic, a project that will help the business marginally but with high certainty could be considered worth doing. You don’t have to use my ordering method, but the important thing is to align your partners on a coherent decision-making framework so you can explain how the team makes their decisions.

Hopefully, your exercise's output has more than enough high impact, high probability of success projects that complete within a half that obviate the need to consider projects on lower tiers of the list.

Moreover, at the end of this exercise, you'll also have a ranked list that teams can use as a reference if there are race conditions on a single resource, and those teams need to choose who to support.

The journey to effective

A reality all too familiar to most of you is that few organizations actually practice the habit of researching and prioritizing their initiatives. Sure, every company goes through some periodic planning exercise, but what comes out of such exercises more often than not boils down to too many initiatives to focus on, with too vague a charter, and little confidence by the actual team to pull the project off because they weren't consulted upfront.

Given these challenges, I have three tips on operating in these environments so that you can be an agent of change in your organization.

Use the Impact X Probability of Success framework to clarify discussions

For an organization that still lives with the myth that they can do many things well, driving a prioritization exercise can be difficult. If you are in the conversations that help define an organization’s priorities, I find leading a stakeholder through the Impact X Probability of Success matrix to be a beneficial exercise. If your engineering manager insists that a refactoring effort is needed, ask them to score their engineering priorities on the same scorecard as your business priorities or vice versa if you’re the engineering manager working with a product manager.

If you happen to be downstream of the decision, there may be an opportunity for you to manage what your priorities might be by going through the Impact X Probability of Success prioritization exercise for yourself and obtaining buy-in on your assessment of what's truly important to work on from your management team.

In either case, the exercise helps eliminate the passion projects, the snap decisions and helps participants articulate why certain decisions are made while balancing the risk that projects may fail.

Create snapshots of decisions, and hold your stakeholders accountable

Launching projects is always an exciting time for teams. It represents the hopes and expectations of something new and with it the infinite ways in which a new project can impact a business before reality sets in. However, if you want to avoid the cycle of launching projects while never landing anything, then you have to hold your leaders and peers people accountable.

The most effective way I've found to hold the management team accountable is to archive ahead of all projects proactively: the memos, presentations, and emails generated at the start about assumptions and projections made and then hold conversations after the fact how we can improve outcomes.

These retrospectives can be group conversations, but they can also be private conversations with your stakeholders, VP, or CEO. The important point is to have them because it shows that someone, perhaps you, actually cares about building something meaningful rather than participating in the parade of launching projects that never matter. Sometimes when I provide this advice to my mentees, I’m asked if this is career limiting. To me, it’s a trade-off between having a difficult conversation or working on things that don’t matter, which in my view, is the true career-limiting factor.

Accept that you're part of the problem

Many people face the challenge of working in a "more is more" organization. Most leaders won't admit this, I know for years, I certainly did not - but over time, I've learned that encouraging my teams to do less always resulted in more.

The first step was understanding that I needed to take a hard look at what I could do to simplify my direct reports and their organizations' activities. The reason is that if you're not focused on how you work, if you're teams aren't operating with clear priorities, then how can you influence your stakeholders and your company at large?

There's a wonderful and apparently apocryphal story* about an inscription on the tomb of an Anglican Bishop at Westminster Abbey in the book Chicken Soup for the Soul, which I recount here:

When I was young and free and my imagination had no limits, I dreamed of changing the world.

As I grew older and wiser, I discovered the world would not change, so I shortened my sights somewhat and decided to change only my country. But it too seemed immovable.

As I grew into my twilight years, in one last desperate attempt, I settled for changing only my family, those closest to me, but alas, they would have none of it.And now as I lay on my deathbed, I suddenly realize: If I had only changed myself first, then by example, I would have changed my family.

From their inspiration and encouragement, I would then have been able to better my country and, who knows, I may have even changed the world.

Effective organizations aren’t born that way. They were forged by people who wanted to drive change. Maybe you're not satisfied with what you see around you at work. But maybe, you can help change that by taking this first step and look inside yourself and your team.

* I first read Chicken Soup for the Soul in college and was enchanted by this story. When I had the chance to visit the UK for the first time, I had hoped to see this tomb in person but based on my research, the story is made up, and the tomb does not exist. Nonetheless, I still love the story.